Storymap Project Lessons – A Designer’s Perspective

Sep 29, 2016

Author: Tiffany Forner

I’ve worked on many Grove Storymap® projects during my 18 years at The Grove. In the beginning, it felt like wading through a swamp of data, struggling to find a way to communicate a client’s complex situation in a clear and simple way. This kind of information design was not like anything I learned as a design major in college.

After years of practice and collaboration with my esteemed colleagues, Laurie Durnell and Rachel Smith among others, it has gotten easier. Below is a summary of some things I have learned.

Don’t Panic in the Data Swamp or Data Void

Grove Storymaps provide a “big-picture” view of information that an organization finds difficult to get its arms around. Clients typically hire us to create Storymaps to help them: 1) define and communicate a strategic process, initiative or vision; 2) get bits of information all on one page to inform decision-making; and 3) build leadership and stakeholder understanding and momentum.

At the beginning of an engagement clients often send us several documents that reflect how they are currently communicating their content. This can be in the form of Word documents or PowerPoint presentations with 40 to 60 slides containing bulleted text. Although some of these materials are helpful, many make your head hurt. At this point, I don’t panic, I take a breath and say to myself, “This is why the client needs us.” If they are trying to communicate in this dry, mind-numbing fashion to their stakeholders, no wonder they aren’t getting much traction.

Sometimes there is no background material and the client hires us to assist in pulling the story out. On a scale of 1 to 10, the data is at a 1—existing as disconnected pieces of information in various people’s heads. No matter the state of the data, I’ve learned that it’s okay, we will get to the heart of the matter. This is where skilled facilitation really makes a difference. I marvel at our facilitators’ ability to engage clients in telling their story in a simple, understandable way.

In a kickoff session, in addition to grasping the basics of the communication need, we will also learn what often is not in PowerPoint slides: what people care about, what scares them about a situation, and what excites them about moving forward. These are the emotional hooks that people need to perk up and get involved. A wealth of information usually comes out of a face-to-face or virtual storytelling session. The information starts to become organized, stakeholders are engaged, and I sigh with relief. Now I have a storyline I can work with.

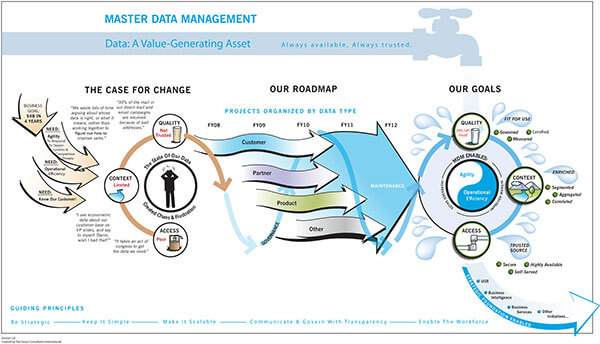

Listen for the Visuals

In these sessions, I spend most of my time listening for the key phrases, idioms and metaphors that come from the group. These are the gems that naturally lend themselves to visuals. For instance, I recently had a client express the feeling of uncertainty that his business faces: “We are in uncharted waters.” Bingo! This turned into one concept with a ship image. Another client described its data-management initiative as an untrustworthy water-supply system transforming into a steady stream of clean, pure, data. Then there are the tried-and-true metaphors that often come out: “bridging the gap” and “ramping up,” for example.

Sometimes it’s not a metaphor, but rather shapes that come forward. If a client needs to show a community or system with a central focus, circular frameworks lend themselves nicely. If forward movement is a large part of the story, I have many shapes and sizes of arrows to employ.

When the images aren’t coming easily, sometimes I simply start with one small piece of the story. I was recently working on a very challenging project and the only visual I heard was the location of the client’s target customer in an office building. Understanding that this new customer was key, the drawing was developed from that starting point.

The Concept Stage is Often the Most Difficult

At this point in Storymap projects, we suggest that clients pull together a small group or design team of stakeholders to review concepts together. We usually create three concept sketches for a typical Storymap project. We do this so that our clients can see their information displayed in different visual formats, to test the focus of the story, AND to continue to build consensus within the group. When we deliver the concepts and prepare a meeting or call to discuss the drawings, I am prepared for anything. Some projects are smooth-sailing—the client connects with one of the drawings immediately, and we then can move on to creating version 1.0 quickly. Or a client design team will like pieces of multiple drawings, and my next step is to pull it all together into a new concept. These are easier projects.

Then there are the more difficult ones. I’ve learned over the years that even if I really think I’ve nailed a concept, I need to have a thick skin. These drawings test an organization’s sense of clarity, and at times, things are just not clear. Putting strategy into visual form can test people’s assumptions in ways that the written word alone does not. So concepts get beaten up, but I’ve learned that the rejects are incredibly valuable because I will hear things like, “It’s not like that, it’s like this…,” and then I get a clearer description. These discussions are also of great value to the client. These missed concepts help a client face up to its challenges and put stakes in the ground about what they need to communicate and what they don’t.

A Flood of Feedback Means the Fog is Clearing

My favorite stage in any Storymap process is what we call version 1.0—when we’ve landed on a workable concept and begin filling in and refining details. At this point, the graphic takes on a life of its own as a clarity builder. We usually don’t have to draw out people’s responses when they see a Storymap draft, because they are more than likely chomping at the bit to talk. We’ve held many review sessions marking up first versions of a Storymap that last for hours—not because we got it wrong, but because the client could finally “see” the story and could now have the conversations that stakeholders need to have.

In one instance, The Grove was visualizing a client’s transformation process and I’ll never forget the moment when a man stood up, came over to the drawing, pointed to a particular spot and said, “This is the point where the level of effort greatly increases.” There was a resounding “Yes!” in the room. This key piece of the story had large resource ramifications and needed to be reflected in the Storymap and in the client’s planning. It is these beautiful moments of realization that make Storymaps so rewarding for both the client and for us.

Not Your Typical Design Gig

For an artist, I landed quite a unique career. Over the years I have worked on a spectrum of interesting projects for a range of clients—from large corporations to social and environmental organizations. With each Storymap, I learn something new.

Because I don’t have your typical design job, trying to explain what I do to someone unfamiliar with this way of working can be an occupational hazard. My description: “I work for a consulting firm that visually maps a client’s situation to enable forward movement.” I usually get a puzzled look. However, those who have seen or experienced Storymapping often say to me, “You have the coolest job!” I couldn’t agree more.

Tiffany Forner, art director, has worked on a wide range of communications-design and product-development projects in her 18 years with The Grove. Tiffany has a bachelor’s degree in design from the University of California, Los Angeles.

For more information about Storymapping please contact services@thegrove.com.

Download the Storymap brochure.